Career Review

The Formative Years

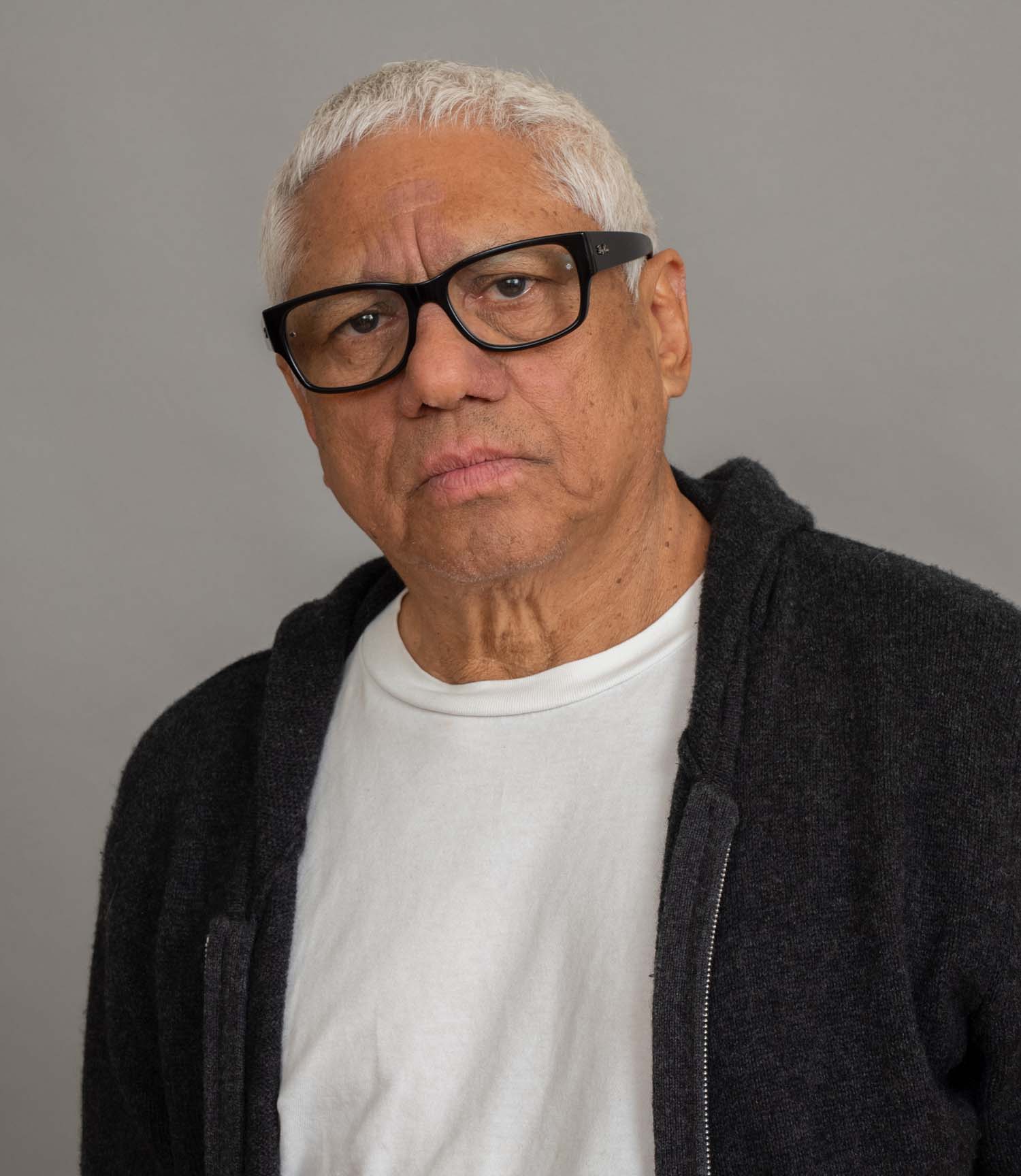

Dino Aranda was born in Managua, Nicaragua in 1945. Realizing he had a gift for art, his family enrolled in Managua’s School of Fine Arts. Mentored by Rodrigo Penalba, Director of Managua’s School of Fine Arts, Aranda was introduced to concepts of modernism and seeped in high standards of craftsmanship, which were brought to Nicaragua by Penalba from his studies at European academies. Penalba demanded quality, but at the same time, he encouraged each student to follow and discover his own direction. Penalba states that Dino Aranda distinguished himself as an artist by the strength of his paintings. His still life paintings reveal real discipline in their use of earth tones, harmoniously accented with subtle colors. [1] Dino Aranda benefited from Penalba’s teachings between 1957 and 1963, receiving a Certificate in Fine Arts (Master’s Degree equivalent) from the School of Fine Arts in Managua, Nicaragua.

According to Argentine art critic, Marta Traba, the post-World War II years in Latin American art were marked by undefined tendencies simmering below the surface which grew into clearer expressions of artistic thought. In the south, primarily in Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and Sao Paulo, abstract form dominated the scene, while in the north Marxist ideology influenced Mexican muralism. [2] Following his studies at the School of Fine Arts, Aranda, along with other artists co-founded the Praxis Gallery Group. The birth of Praxis Gallery Group in 1963 provided a middle path between the two movements and established Managua, Nicaragua as one of the leading centers in Latin American art. [3] Formed by Alejandro Arostequi, Cesar Izquierdo, Leonel Venegas, Leoncio Saenz, Luis Urbina, Orlando Sobalvarro, Genaro Lugo, and Dino Aranda, the youngest member of the group, Praxis believed there is but one reality that manifests itself in different forms. Artistic creativity is but one aspect of this reality, and it works independently with socio-economic forces to produce a variety of expressions. [4]

For the Inauguration Exhibit at Praxis Gallery in 1963, Aranda submitted still life and landscape paintings that exemplified his experimentation with abstract form and heavy impasto, while at the same time, incorporating the symbolism of his Mayan roots. He and Arostequi began to experiment with three-dimensional surfaces, and Aranda created three-dimensional works by mixing pigments, wires, and other objects he found. Jose Gomez-Sicre, Chief of the Visual Arts Division at the Pan American Union, attended the exhibit and was so impressed with Dino Aranda’s work that he purchased one of Aranda’s large abstracts for the Esso Standard Oil Collection. The abstract was included in the Pan American Union’s exhibition at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York and Berlin, where Aranda exhibited, along with Armando Morales, Fernando Botero, Omar de Leon, and Fernando de Szyszlo. [5] Jose Gomez-Sicre states that Aranda became a talented draftsman, using flawless fluid lines to describe his subject. As a painter, he became an outstanding colorist. [6]

In a second exhibition at Praxis Galeria in 1963, titled “Mural Poetry Exhibit,” each exhibiting artist chose a poem to illustrate. Dino Aranda chose a poem by Michele Najlis, the only poet with the courage to denounce Somoza’s dictatorship. This was Aranda’s collaboration between the visual arts and poetry with a socio-political content. This type of collaboration found fruition in his later work with Ernesto Cardenal.

In 1965 Dino Aranda moved to Washington, D.C. on a Ford Scholarship to study at the Corcoran School of Art, and to complete work for an individual show at the Organization of American States to be held in 1969. Unlike many other artist expatriates, he maintained close cultural ties to Nicaragua. [7] Aranda sent a series of figurative sketches in ink and wash on paper that he had prepared for classes at the Corcoran to Managua for an individual show held at Praxis in 1966. All sold rapidly to private collectors. Gomez Sicre stated that the sketches demonstrate Aranda’s maturity as an artist. According to Gomez Sicre, they show spontaneity and freedom, without hesitation or insecurity. [8]

The Emerging Master Artist

The twenty-five paintings exhibited at the OAS in 1969 defined Aranda’s early style and established his reputation as an artist. Influenced by Praxis aesthetics, the works reflect political and socio-economic conditions in Nicaragua during the Somoza dictatorship. They depict mutilated bodies crowed into cages suspended in air and express the fear and pain of a distant past as it appears in the present. [9] Marta Traba, one of the most influential critics on Latin American Art in the 20th century, characterized these works by Aranda as representative of one of the new trends in Latin American art, that of grotesque realism, similar to the works of Francis Bacon. [10]

The eminent Guatemalan artist, Roberto Cabrera, astutely distinguished Aranda’s work from Bacon’s. He states that while Bacon’s grotesque figures are caught in a nightmare, Aranda’s grotesque figures are representations of reality in Nicaragua. Aranda shows mankind’s eschatological existence, expressed during a specific time in history. His works depict reality, not fantasy or dreams. He diverges from pure geometric abstraction to reveal the other psychological side of visual art, that of realism, where feeling is more important than thought. It is a figurative art completely different from the classical tradition. It is Latin American in substance; a search in the current political and socio-economic landscape for images that reveal the collective subconscious of mankind. [11]

In 1970, the exhibit moved from the OAS in Washington, D.C. to Guatemala City, where it was shown at the Vertebra Gallery and the University of San Carlos. From there it went to El Salvador, where it was introduced by Benjamin Canas at the Galeria Forma. Finally, it made its debut in Leon, Nicaragua, in a group show entitled “Aranda, Arostegui, and Selva.” Although part of the collection sold to private collectors, the remaining works came back to the United States to be organized by James Harithas for a 1973 show at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York. Aranda added landscapes of Nicaragua and incorporated the poetry of Father Ernesto Cardenal.

There is a long history of dialog between poetry and painting. The benefit of this relationship is that it expands creative potential, allowing each art form to offer a clearer message to society. The interplay rests on a delicate balance between differences. For example, while poetry is the art of rhythm and time, painting is the art of space. To succeed, poetry must articulate sounds in a series, using words to create a mood. A painting, on the other hand, captures and freezes a mood in time. [12] Cardenal and Aranda succeeded in achieving this balance between poetry and the visual arts to create a powerful message about the Somoza dictatorship.

James Harithas says the collection documents the fate of a people suppressed by tyranny. According to Cardenal, such suffering is a third-world heritage, and it must be understood within the context of a loving, God-filled universe, distorted by inhuman acts that defy the pervasive Spirit. Aranda’s images are of a death-driven people, buried in an oppressive landscape of gray green. [13]

Leading art critic, Rafael Squirru, states the paintings reflect the sadness Aranda shared with his people. That sadness is revealed in a move away from color, which characterized his earlier career, to one of monochrome. [14]

The show at the Everson was expanded into book form. The theme was broadened from one that focused on Nicaragua to one that included Native American cultures of North, Central and South America. [15] Homage to the American Indians is a collection of poems by Cardenal that portray a peaceful and more human society that is more in touch with natural cycles of history. The modern world of supply and demand is replaced with a new world order derived by the culture of the Native American past. For the book, Aranda competed a new set of paintings. They were acrylic on canvas and incorporated the symbolism of his Mesoamerican heritage to arrive at a synthesis of spiritual symbols common to Native American cultures of all three of the Americas.

In 1976, the OAS organized an exhibit entitled, “Contemporary Printmakers of the Americas.” The first of a series, it toured the United States and Latin America with the purpose of furthering cultural interactions. For the show, the OAS chose Aranda as the sole artist to represent Nicaragua, with an etching that had shown at the Everson Museum, entitled “Prisoners,” completed in 1972. [16]

In November 1976, the Smithsonian organized “The Art of Poetry” exhibition at the National Collection of Fine Arts. This extraordinary show was the result of much research and explored a variety of approaches to the collaboration between artists and poets. It included, among others, Robert Motherwell, William de Kooning, Claes Oldenburg, Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, Larry Rivers, and Sam Gilliam. Only two Latin American artists were represented – Antonio Franconi and Dino Aranda. Aranda’s acrylic and pencil on canvas, entitled “non-Mayan Mayapan,” illustrated a poem by Ernesto Cardenal, and was part of the series done for Homage to the American Indians. [17] Octavio Paz (who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1990) and Cardenal (who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2005 and 2019) were the only two Latin American poets selected for the show.

Conceptualized while working on the book with Cardenal, Aranda completed a series of figurative drawings in graphite on watercolor paper, within a landscape context. When the OAS opened the Museum of Modern Art of Latin America in 1976 (later changed to Art Museum of the Americas), it purchased two to these drawings, to be included with the two already purchased in 1969, so they could be added to the Permanent Collection. The Smithsonian also added one of the 1977 figurative drawings to the Permanent Collection of the National Museum of American Art.

Traba states the 1977 drawings, series 1 through 8, “Untitled,” were executed with rare force and beauty. She states Aranda succeeded in capturing space so as to give the viewer a feeling of being locked within a cell. Shapes, distributed irregularly, take form as ancient ruins without exits, as cemeteries, or as urns filled with bones. Aranda allowed the texture roughness and crevices of the paper to define the shapes and then let them trail off into inconclusive space. These forms make a persuasive statement about the political drama under the Somoza dictatorship. [18]

Exploring Additional Avenues of Expression

While preparing for the Everson show in 1973, Dino Aranda co-founded Fondo del Sol, Washington, D.C.’s first Multi-cultural Museum. Fondo was originally founded to provide a workshop for a group of seven artists and writers from South, Central and North America. The center grew into a community museum, sponsoring over 150 exhibitions of primarily Hispanic and other minority artists.

One of the first projects at Fondo was to compile a research directory of Latin American artists living in the United States, in order to organize and exhibit of their work. The result was “Ancient Roots/New Visions,” which traveled to nine cities in the United States, as well as Mexico City, between 1977 and 1980. The show was a milestone, in that it was the first important exhibition of Chicano, Puerto Rican, and other Latin American artists living in the United States. Aranda was represented with his “Three Figures,” an acrylic on canvas done for the OAS show, and “Managua,” a mixed media on board, from the Everson show.

By 1982, Fondo expanded to provide space for the growing Permanent Collection. The museum also sponsored events to foster intercultural exchanges, and in 1984 the Caribbean Arts Festival drew more than 10,000 people. [19] Public funding came from the D.C. Commission for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the D.C. Neighborhood Planning Commission, as well as private sources such as the AT&T and Ford Foundations.

At the same time, Aranda broadened his reach as an artist by becoming involved in media production. He was introduced to the possibilities of artistic expression offered by video as a medium through a two-person show with Juan Downey. “Figure and Context,” shown at Fondo del Sol in 1979, was a collaboration with Downey’s work with the Yanomami Indians in the Amazon. The collaboration with Downey influenced Aranda to expand his work with Mesoamerican images into video form.

In 1980 Aranda co-founded Tresamericas Productions. He became active in co-producing and directing a number of bilingual videos on the Latin American experience. The most extensive of these, Liberation Theology: Its Impact, co-produced and co-directed with Mary Lou Reker, was shown on PBS in 1983, and is in the permanent collection of numerous video libraries, including the Ringling Museum in Florida.

The Mesoamerican Years

In 1992, a “Twenty-Five Year Retrospective,” held at Fondo del Sol, exhibited fifteen of Dino Aranda’s works, which were on loan from private collectors and museum permanent collections. The show reflected the evolution of Aranda’s thought, expressed visually. In earlier works, cages turned to coffins and color left. But by 1979, with the fall of the Somoza dictatorship, color began to creep back slowly. The delicately colored paintings done for the book with Ernesto Cardenal reflect Aranda’s belief that spirituality is the foundation of art throughout history, and paintings are a way of communicating a spiritual message. [20]

Aranda first began working with images of Quetzalcoatl in 1973, when he completed the paintings to illustrate Homage to the American Indians. Becoming more acquainted with this pre-Colombian deity during his extensive research of Native American cosmetology, Quetzalcoatl has been a reoccurring theme in his work since. Between 1988 and 1993 Aranda completed another series of Quetzalcoatl images in acrylic on linen canvas. Many of these are in the Permanent Collection at Fondo del Sol. In 1997 he began a third series of paintings on Quetzalcoatl, in acrylic and gold leaf on watercolor paper, wood, and linen canvas, which were completed in 1997.

The story of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, is a central theme in Pre-Colombian art and literature. Although his legend lay dormant during the post-colonial era, it reemerged with the indigenista movements of post-revolutionary Mexico. He appears in the works of Tamayo, Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco. [21]

In order to understand the importance of Quetzalcoatl, one must understand modern Mesoamerican thought. The culture of the elite in Europe has been acquired by adoption. [22] But the mestizo culture of Mesoamerica is a blend of Pre-Colombian culture, over which Iberian and Western influence has been superimposed. [23]

Therefore, in order to understand Latin American history, states Octavio Paz, one must distinguish between explicit ideas, as reflected in political and socio-economic histories, and implicit beliefs, which are revealed through mythology. By tracing ancient beliefs through buried images one can gain insight into the religious world-view of contemporary Mesoamerican culture. [24] It is a culture in which Catholicism mixes with pre-Colombian deities to produce an authentic indigenous variant.

Within the pre-Colombian cosmology, Huitzilopochtli was the sun god of warriors, while Quetzalcoatl was the sun god of priests. Huitzilopochtli demanded human sacrifice, but Quetzalcoatl refused to fight, and he died in order to be reborn. [25] Human sacrifice, according to Paz, also must be understood within the Mesoamerican context. [26] Since life did not belong to man but to the gods, death lacked personal meaning. [27] Man was simply an actor in a cosmological drama on earth.

Within this context, the gods represented cycles of death and rebirth. Conflict and war was the critical moment when supernatural forces came together causing a transformation to occur. A heart, still beating, was torn out of the flesh of a living victim and offered as a gift to the warrior god, Huitzilopochtli, who died every evening with the setting sun. [28] Quetzalcoatl abhorred human sacrifice because he loved all living things. [29] He was reborn every morning with the rising sun. [30] Aranda is drawn toward Quetzalcoatl’s symbolism because for a Mesoamerican, Quetzalcoatl is closest to the mythical Christ, and provides a synthesis of Pre-Colombian and Western cultures. Christ is the redeemer while Quetzalcoatl is the re-creator. [31] Both allow man to be reborn.

Out of his interest in Latin American music, as well as his research into the roots of salsa, merengue, and tango, in 1996 Dino Aranda completed “Tango,” in dedication to the Latin festival in general, and to the famous tango singer, Carlos Gardel, in particular. For Latinos, the festival is a celebration of life. To the Latino, it is a necessary element of life that follows work. It is a communion, a vital, orgiastic, multicolored frenzy that frees man and unites him with the universe. [32] Latin dance is part of this communion, and Aranda succeeds in capturing this spirit in “Tango.”

With “Tango,” an acrylic and gold leaf on wood and canvas, Aranda explored art conservation techniques learned in 1989, when he completed a Restoration and Gilding certification program at Sotheby’s. He added these techniques to those he learned long-ago from Penalba at Managua’s School of Fine Arts. Using the highest standards of conservation in all his work, Aranda feels that one reason the visual arts are so important is because they document man’s history, and therefore, must be preserved.

While in Washington, D.C., Aranda became increasingly restless, being convinced that the issue-oriented art of the 1970s and 1980s had served its useful purpose. Just as the focus on the political had drained Mexican muralism of its vitality, so he felt the focus on minority issues resulted in an unimaginative didactic art devoid of aesthetic feeling. [33] Contributing to his artistic boredom were winds of change in the political and socioeconomic arena. Peace, accompanied by a fragile economic stability had come to Nicaragua, providing fertile ground for the seeds of democracy to take root. [34] Aranda needed a new direction.

A New Direction

Dino Aranda left Washington, D.C. in 1999 in search of new images. Having made profound political statements in the 1970s when they needed to be made, Aranda moved to southern California. He was tired of abstract forms that could only be understood by the erudite. He sought an artistic expression that could be understood by the mainstream. His goal was to produce timeless works with a universal message that transcends political issues and minority art, and all the other “isms” in artistic thought.

On his way out to California, he visited Central Florida for a short time, where he began a series of landscapes that reflect the lush green of the tropics in the heavy air. When he arrived in California, he moved to Imperial Beach, where from his studio he could see the ever-changing hues of a wild-life estuary and at night the shimmering city lights of Tijuana across the Mexican border. His landscapes there capture the translucent light of southern California, where the dampness of the ocean mixes with the desert winds, producing a morning mist that shrouds the view in blue, only to be pierced by the relentless power of the noon day sun. Following California, he moved to Arizona and is currently living in Sedona, where he is inspired by the bold colors of the southwest.

The result has been a series of works in watercolor on paper that capture the evanescent quality of light but maintain a fine balance with detail. The original landscapes have been reproduced in a series of extremely limited-edition Iris Giclees on Archival Paper and Inks.

The landscape is autobiographical in that it reflects a mid-life healing. The elongated figures in coffins have given way to tall palms, whose soft-hued fronds sway with the fragile ocean breeze. The composition is imbued with the same subtle use of pastels and precise but fluid lines that established Dino Aranda when he was studying with Penalba at the School of Fine Arts in Managua and evolved in the course of his prolific career.

Inspired by many sources, Aranda has transformed them to suit his purpose. One purpose was to reflect the spirituality that underlies the landscape. Aranda believes that there are divine patters in nature. He strives to find these by, for example, allowing the texture of the paper to define his shapes, and the colors of his watercolors to define each other.

Taken as a whole, the current works are tied together by a spiritual thread that is manifest in nature’s diversity. These works signal back to Aranda’s roots and his beginning work with Praxis, built on a belief that reality manifests itself in different forms. They are a culmination of Aranda’s thought that spirituality is the foundation of art, and that paintings are a way of communicating a spiritual message.

This Career Review was written jointly by Dino Aranda and Alice Vacek Aranda, who holds a Master’s Degree in Latin American History from the University of Florida in Gainesville, and a Juris Doctorate in Law from California Western School of Law in San Diego. She practices immigration law in Arizona, focusing on uniting families separated by borders and asylum applicants fleeing persecution.

[1] Jorge Eduardo Arellano, “Boletin Nicaraguense de Bibliografia y Documentacion,” Biblioteca, Managua, Nicaragua, Banco Central de Nicaragua, 1977, vol. 20, p. 50.

[2] Marta Traba, Art of Latin America: 1900-1980, Baltimore, Maryland, John Hopkins University Press, 1994, p. 84.

[3] Id.

[4] Jorge Eduardo Arellano, “Boletin Nicaraguense” at p. 50.

[5] “Latinamerikanische Kunst-Ein zeitgenossisches Panorama,” Catalog Introduction by Jose Gomez-Sicre, Pan American Union exhibition Berlin, Germany, 1964.

[6] Dino Aranda of Nicaragua, “Catalog Introduction by Jose Gomez-Sicre, Pan American Union, Washington, D.C., 1969.

[7] Marta Traba, “Mirar en Nicaragua,” El Pez y la Sepiente, Managua, Nicaragua, Editorial UNION de Cardoza y Cia, Ltd. January 25, 1981, p. 75.

[8] “Exposicion de Dibujos de Dino Aranda,” Catalog Introduction by Jose Gomez-Sicre for individual show at Praxis Galeria Managua, Nicaragua, 1966.

[9] “Dino Aranda,” Catalog Introduction by Roberto Cabrera, for the show at Galeria Vertebra and Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, October 1970.

[10] Traba, Art of Latin America, p. 162.

[11] Cabrera, “Dino Aranda.”

[12] “The Art of Poetry,” Catalog Introduction by Peter Bermingham, Curator of Education, National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., November 19, 1977.

[13] “Homage to Nicaragua,” Catalog Introduction by James Harithas, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York, January 26, 1973.

[14] “Dino Aranda,” Catalog Introduction by Rafael Squirru, Chief of Department of Cultural Affairs, OAS, Washington, D.C. and Roberto Cabrera, Guatemala, for show at Galeria Vertebra at Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, October 1970.

[15] Ernesto Cardenal, Homage to the American Indians, translated by Monique and Carlos Altschul, illustrated by Dino Aranda, Baltimore, Maryland, John Hopkins University Press, 1973.

[16] “Contemporary Printmakers of the Americas,” Catalog to exhibition by the Organization of American States, 1976.

[17] Catalog Introduction for the Art of Poetry exhibition, National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 1976.

[18] Traba, El Pez y la Serpiente, p. 75.

[19] “Fondo del Sol, the Nation’s Second Largest Spanish-speaking and Hispanic-oriented Museum,” Nuestro Magazine, March 1985.

[20] Mary McCoy, “Painter Depicts 25 Years of Nicaraguan Turmoil,” Washington Post, June 25, 1992, p. DC 4.

[21] Dino Aranda and Mary Lou Reker, “Quetzalcoatl: The Survival of Pre-Colombian Mesoamerica in the Post-Colombian World,” Video Transcript by Tresamericas Productions.

[22] Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude, New York, New York, Grove Press, p. 50.

[23] Carleton Beals, Mexican Maize, New York, New York, The Book League of America, 1931.

[24] Paz, Labyrinth, pp. 332-334.

[25] Ibid., p. 95.

[26] Ibid., p. 103

[27] Ibid., p. 55

[28] Esther Pasztory, Pre-Colombian Art, New York, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 24-25.

[29] Video Transcript by Tresamericas, “Quetzalcoatl.”

[30] Paz, Labyrinth, pp. 24-25.

[31] Ibid., p. 108.

[32] Ibid., pp. 364-65.

[33] See generally, Edward Lucie-Smith, Movements in Art Since 1945, New York, New York, Thames and Hudson, 1995, and Latin American Art of the 20th Century, New York, New York, Thames and Hudson, 1997.

[34] For a useful analysis on cultural modernism see Nestor Canclini, Modernity after Postmodernity in Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism in Latin America, edited by Gerardo Mosquero, Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT University press, 1996, pp. 22-66. Canclini argues that culturally, the development of modernism must be viewed in light of political and socioeconomic modernization because the two trends tend to influence each other. The two trends must be viewed separately because their development does not always correlate. Advances in modernism are produced at points of tension between the two trends, but in the 1990s, the two flowed more closely together than ever before.